Hybrid Warfare Before World War II

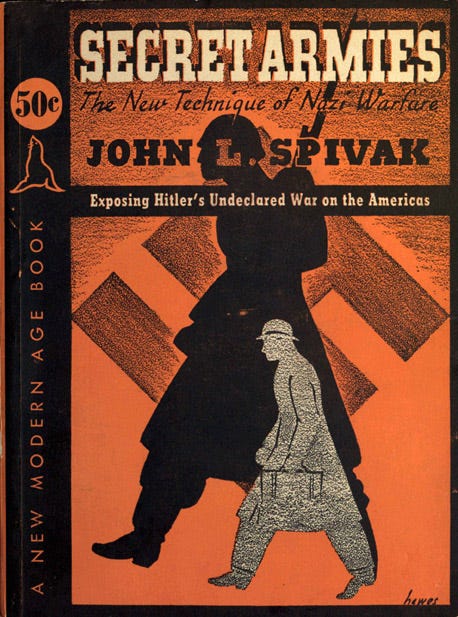

"Exposing Hitler's undeclared war on the Americas."

“Secret Armies: The New Technique of Nazi Warfare” (1939) is a book by American journalist John L. Spivak.

The cover features an inconspicuous man casting the shadow of a German solider with rifle, helmet and infantry backpack on the wall. It is meant to illustrate the danger of foreign agents.

In the introduction, Spivak cites a quote falsely attributed to Nationalist general Emilio Mola about a “fifth column”, consisting of spies and propagandists, that would be most important in seizing Madrid during the Spanish Civil War.

Spivak uses the quote to prove that the Fascists have always mastered subterfuge and with this book he seeks to expose a secret war the Axis powers have been waging against democratic countries.

Czechoslovakia

Spivak opens the first chapter, “Czechoslovakia—Before The Carving”, by writing that infiltration by Gestapo agents played a key role in both Austria and Czechoslovakia before the incorporation of their territories into Nazi Germany.

The rest of the chapter is spent establishing the Gestapo as an insidious covert propaganda and sabotage agency, dwelling deeply into its methods and goals.

Spivak cites the Henlein party and Sudeten German organizations generally as recruitment sources for the Gestapo in Czechoslovakia. Their loyalty to Germany makes them natural spreaders of Nazi propaganda and a good foothold for German influence.

The highlight of the chapter is an anecdote about an inexperienced agent named Arno Oertel receiving a new assignment from Richter, his Gestapo overseer.

Oertel is instructed to make his way to Prague and presumably begin disrupting local anti-fascist groups. Richter reassures him the German Consul will get him extradited if caught. However, he also issues him a cyanide pill for dire situations.

Oertel’s first point of contact in Czechoslovakia is Anna Suchy, a Sudeten German Nazi and prominent member of the “Deutscher Volksbund”. Richter tells Oertel she will direct him to his second handler.

When reporting to “Frau” Suchy, Oertel is given a date and time he is to meet another Gestapo agent by the fountain at Karlsplatz in Prague who will give him further instructions.

At the designated time Oertel sits on a bench at Karlsplatz watching the fountain. A man in a gray suit with a blue handkerchief hanging out of the front pocket approaches. The handkerchief being a clue Oertel was to identify his contact by.

They exchange passphrases and then the other agent sits down. He tells Oertel his second intermediary is an English missionary named Robert Smith.

Spivak concludes by explaining that the missionary in question is a Church of Scotland minister and is known to arrange for German women to be employed as housekeepers for government officials and military officers in Britain.

The specificity of the Arno Oertel account is extraordinary, containing not only exact words, but also facial expressions and internal monologue. These details could impossibly have been obtained by Spivak and must be read as dramatic embellishments.

The Panama Canal

In chapter five, “Surrounding the Panama Canal”, Spivak writes about espionage conducted by the Fascist powers, especially Japan, in preparation of sabotaging or capturing the Panama Canal in the event of war with the US.

Spivak opens the chapter by narrating a visit he made to a local shirt shop in Colón, Panama. The black and red shingle on the roof spell out that it belongs to Lola Osawa, a Japanese immigrant.

The shop hardly carries any stock and the two young girls ostensibly employed there do not work and are disinterested in making a sale, even when Spivak walks in and tries to buy a shirt.

What is even more peculiar is that someone, described by Spivak as a West Indian boy, takes pictures from across the street of anyone nosing around the shop. The author himself was photographed when entering the shop.

Spivak is not clear on what role the boy plays in the operation inside the suspicious store. What he is described doing seems too conspicuous to serve any security or intelligence purpose.

However, at one point Spivak refers to the boy as a “lookout”, implying he is keeping an eye out to see if the authorities are catching on.

Spivak says the proprietor’s real name is Chiyo Morasawa and she has been a Japanese agent for more than 10 years. “Lola Osawa”, seamstress and shop owner, is nothing more than a false identity.

Her real task is to harbor photographs of military importance taken by her husband until they can be sent back to Japan.

Spivak says this is just one of many false businesses set up as cover for Japanese intelligence in the immediate surroundings of the Panama Canal.

They are characterized by not having enough business to make rent, but still managing to remain open even in the more expensive parts of town.

They are also usually staffed by Japanese immigrants who seem to be staying in Panama indefinitely, but for one reason or another did not bring family nor seek to establish one.

Multiple such businesses of the same type can be operating in one city, far exceeding local demand. According to Spivak there are eight Japanese barber shops in Colón and 47 in Panama City.

In Panama City there is even a labor union open only to Japanese barbers. What is strange about the union is when a new barber arrives from Japan it gives them money for rent and equipment, effectively setting up competition.

Spivak surmises the union was erected to hold meetings between Japanese spies, something confirmed by the secrecy surrounding its gatherings and the attendance of Japanese diplomats.

Friends of the New Germany

After chapter five subsequent chapters are more interwoven and tell a progressive narrative about Nazi subversion in the United States.

A reoccurring actor is “Friends of the New Germany”, an organization spreading German propaganda in the United States. It was founded by Edwin Emerson, a former American Colonel and war correspondent known for his “patriotism”.

The organization got off to a bad start because its early propaganda was too transparently pro-Hitler and repulsive to people not already persuaded by Fascism.

It made the mistake of having participants in “storm trooper” uniform present at rallies, which alienated ordinary Americans and stirred public backlash against its events.

Due to these initial blunders Emerson was recalled to Germany for further public relations training and a harsh reprimand from his superiors.

Spivak writes that while most propaganda material used by pro-Nazi groups in America arrives through mail, some is smuggled in by ship.

The chief redistributor of smuggled propaganda in the USA is Guenther Orgell, at the time replacing Emerson as head of Friends of the New Germany.

Spivak narrates one particular evening when Orgell visits a German ship named “Europa” and belonging to “North German Lloyd”:

It is twenty minutes to ten, March 16., 1934. The ship is scheduled to leave New York City for Europe at midnight. It is crowded not only with passengers, but also with friends and family seeing them off.

Orgell is dressed in a business suit and carries a folded newspaper. He makes his way to the library where there is a German post office and meets with the postmaster

Despite the presence of other visitors, Orgell casually hands over four unstamped letters, which the postmaster puts in his pocket. These letters contain reports about espionage and propaganda activities to be sent to Germany.

Orgell sits down at a desk and writes yet another letter. Spivak surmises it contains information so sensitive Orgell did not dare prepare it ahead of time least it be lost or stolen.

After finishing the letter Orgell hands it to the postmaster and receives a thin package in return, which he hides in his newspaper and leaves.

Journalist & NKVD-Agent

A surprising fact about Spivak is while he was uncovering Nazi subversion as a journalist and warning against propaganda from Fascist countries, he himself was secretly a Communist and agent for the Soviet Union.1

This is revealed in “Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America” (2009) by John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassiliev.

Spivak was known under the cover name “Grin” and was referred to by it in decrypted messages from the Venona project. He is also implicated as an agent in several NKVD documents. Spivak helped the NKVD by investigating German and Japanese intelligence in the US, as well as keeping an eye on the Trotskyists.2

These revelations might seem to put the credibility of Spivak’s exposés in doubt. However, it was Spivak who funneled information to the NKVD, not the other way around, and the caliber of his work is likely what attracted the agency to him in the first place.

There is no evidence Spivak was a disinformation agent hired to spread a series of cooked up Nazi plots to bolster far-left anti-fascism.

Despite Spivak’s public denial of being a Communist, he largely wrote for and was promoted by Socialist newspapers and magazines.

I first discovered “Secret Armies” in an issue of “Soviet Russia Today”, a magazine from the 1930’s, on a Soviet Archive website.3

It was listed on a mail order form among other Socialist and anti-fascist publications. The title intrigued me and I was inspired to write this essay.

Hybrid Warfare Today

The term “hybrid warfare” gained prominence after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and even more so after the 2016 US presidential election. The concept is often thought to be a product of the Information Age and invented by Russia.

However, Spivak expresses a similar concept in his book, where he writes about a “new type of warfare” based on infiltration and propaganda.

If Crimea was an act of hybrid aggression, what about “Anschluss” with Austria or the partition of Czechoslovakia? In the latter case the invasion was justified as a necessary intervention because of the dire situation in the country.

Spivak describes the relationship between the United States and Germany after the Spanish Civil War as a state of undeclared war, primarily waged by the latter against the former.

The civil war is seen as a result of a covert campaign by the Gestapo to flip the country from Democratic to Fascist.

Spivak fears the Fascists can repeat the trick elsewhere and his book mostly distinguishes areas where he thinks they are using General Mola’s supposed “fifth column” formula to either turn the country outright or render it incapable of resistance.

In this perspective maneuvering for an economic advantage by establishing trade routes for strategic resources becomes “economic warfare”, recruiting members to a military alliance becomes “diplomatic warfare” and disseminating propaganda to justify a casus belli or spread the state ideology becomes “information warfare”.

All of these elements are found throughout the menagerie of Fascists plots presented in “Secret Armies” and they are also key components of what is called hybrid war today.

Spivak grapples with a feeling of being at war with a hostile country before open battle has begun and his work should be seen as a primordial understanding of hybrid warfare.

The age of his book, written more than 84 years ago, should also challenge the idea of the concept as a modern phenomenon.

If you enjoyed this essay I recommend you read “Secret Armies” for yourself. It is available both at The Project Gutenberg and Internet Archive.

Stay in touch by following me on Twitter.

Haynes, J. E., Klehr, H. and Vassiliev, A. (2009) Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. 1st edn. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 152, 160-167.

Ibid.